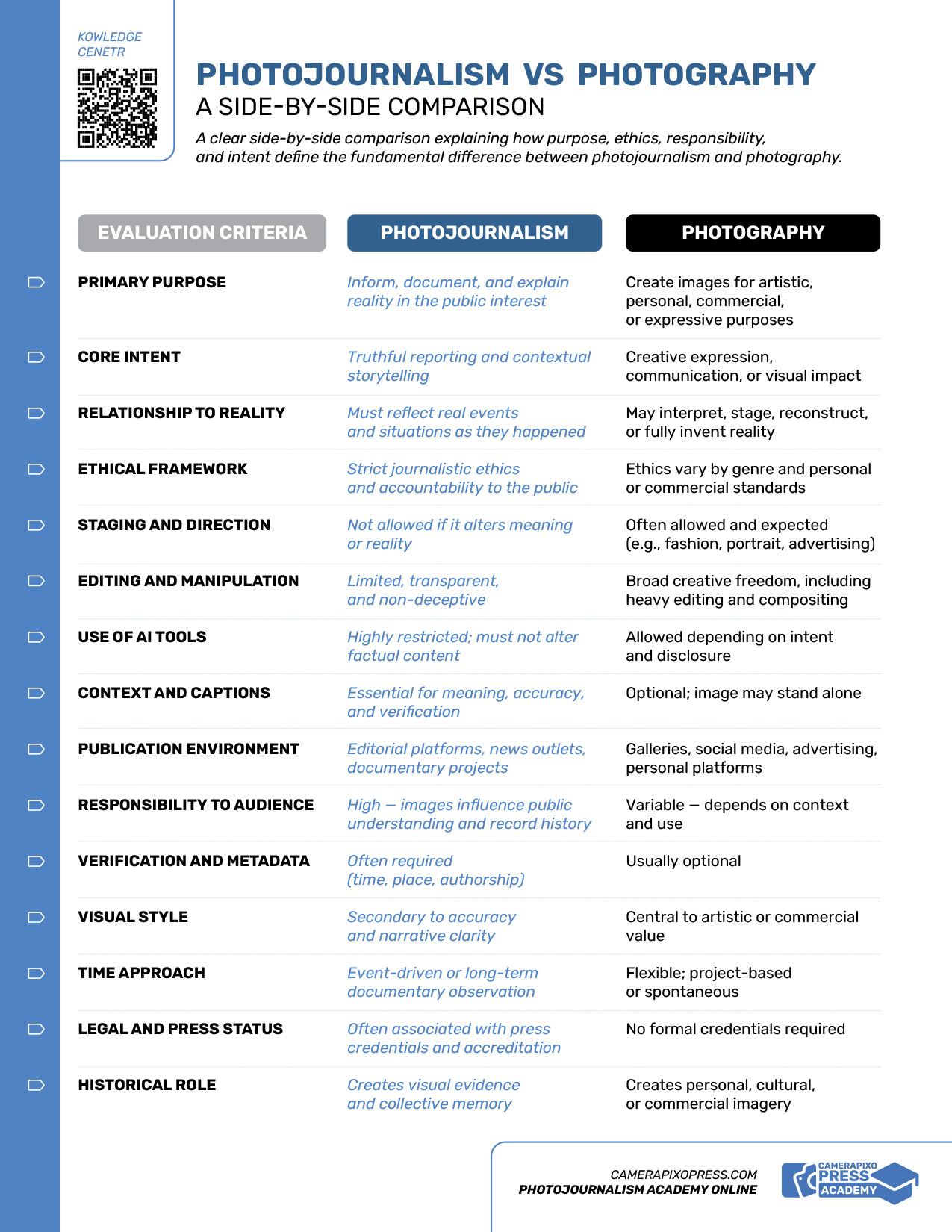

At first glance, photojournalism and photography may appear to be the same. Both rely on a camera, both use light and composition, and both result in images that can be visually powerful. Yet beneath this surface similarity lies a fundamental difference in purpose, responsibility, and role in society. Understanding this distinction is essential not only for aspiring professionals, but also for audiences who consume images every day.

In a world saturated with visuals — from social media posts to AI-generated imagery — the line between documentation and expression is often blurred. This guide clarifies where photography ends and photojournalism begins, and why that difference still matters.

Photography: a broad and open visual language

Photography is an umbrella term that encompasses an enormous range of practices. It is a creative and technical medium used for self-expression, commerce, art, documentation, memory, and communication. A photographer may work to create beauty, sell a product, explore personal emotions, experiment with form, or simply capture moments of everyday life.

What defines photography is freedom of intent. A photographer is generally free to stage scenes, manipulate light, direct subjects, edit images extensively, or even construct realities that never existed. In commercial, fashion, or fine-art photography, creativity and interpretation are not only allowed — they are often expected.

Because photography is so broad, it does not inherently carry social or journalistic responsibility. Its value is measured by aesthetics, emotional impact, originality, or effectiveness in achieving a specific goal, such as branding or artistic expression.

Photojournalism: photography with journalistic responsibility

Photojournalism is not simply a type of photography; it is a journalistic profession that uses photography as its primary reporting tool. A photojournalist operates under the same core principles as other journalists: accuracy, verification, context, and accountability to the public.

Unlike general photography, photojournalism is defined by purpose rather than style. The goal is not to create visually pleasing images, but to inform, document, and explain reality. Photojournalistic images function as evidence and narrative elements within a larger informational framework — news stories, reports, investigations, and historical records.

This responsibility fundamentally limits creative freedom. Staging, directing subjects, altering scenes, or manipulating content in ways that change meaning are not acceptable. Every decision — from framing to editing — must preserve the integrity of what actually happened.

The role of intent: the key difference

The most important distinction between photography and photojournalism lies in intent.

A photographer asks:

- What do I want to express?

- How do I want this image to look?

- What emotion or aesthetic am I aiming for?

A photojournalist asks:

- What is happening?

- Why does this matter to the public?

- How can I show this truthfully and responsibly?

This difference in intent shapes everything that follows — from how images are captured, to how they are edited, captioned, and published. Two images may look similar, but their meaning changes entirely depending on why they were created and how they are used.

Ethics and manipulation: where the line is drawn

In photography, manipulation is often part of the creative process. Retouching, compositing, color grading, and even AI tools can be legitimate techniques depending on context. In photojournalism, however, manipulation is one of the most sensitive ethical boundaries.

Photojournalism demands:

- Minimal and transparent editing

- No alteration of factual content

- Clear context through captions and metadata

- Respect for subjects, especially in vulnerable situations

An image that misleads — even unintentionally — can undermine public trust not only in the photographer, but in the media as a whole. This is why photojournalism places ethics at the center of the practice, not as an optional guideline but as a professional obligation.

Context and publication: how images are used

Another critical difference lies in how images are presented and consumed. Photography often stands alone. An image may be displayed in a gallery, shared online, or used in advertising without needing extensive explanation. Its meaning can be subjective and open to interpretation.

Photojournalism, by contrast, relies heavily on context. Captions, accompanying text, editorial framing, and publication standards are integral parts of the image’s meaning. A photojournalistic image without context risks being misunderstood or misused.

This is why photojournalists typically work within editorial systems and under press credentials, ensuring their work is identifiable, accountable, and traceable — a structure emphasized in professional frameworks such as those promoted by Camerapixo Press.

Can one person be both a photographer and a photojournalist?

Yes — but not at the same time, and not with the same image.

Many professionals work across multiple fields, practicing photography in commercial, artistic, or personal contexts while also working as photojournalists. The distinction is not about identity, but about role and rules. When acting as a photojournalist, the individual must follow journalistic standards. When acting as a photographer, creative freedom expands.

Problems arise when these roles are confused — for example, when staged or heavily edited images are presented as documentary truth. Understanding the difference protects both professionals and audiences from blurred boundaries and lost credibility.

Why this distinction matters today

In the age of social media, citizen reporting, and AI-generated visuals, images travel faster than verification. Audiences often struggle to distinguish between documentation, opinion, promotion, and fiction. This makes the role of professional photojournalism more important, not less.

Knowing the difference between photography and photojournalism helps:

- Viewers develop visual literacy

- Creators understand their ethical responsibilities

- Media outlets maintain credibility and trust

- Society preserves an accurate visual record of its time

Without this distinction, images risk becoming persuasive tools detached from truth rather than instruments of understanding.

Final reflection

Photography shows us what can be seen. Photojournalism shows us what needs to be understood. Both are valuable, but they serve different purposes. In a world where images increasingly shape opinion, memory, and belief, recognizing this difference is essential — not only for professionals behind the camera, but for everyone in front of the screen.